The last time I had played the high altitude game – in northern India two years ago – I got wrecked. Entirely. Low temperatures, steady wind, burning sun and constant bacterial load had been too much for our kids (zero and three years back then) and for us as well. I had left Europe just having sent my first 9a+ in Jansegg in Switzerland – Des scènes bizarres dans la mine d’or – and only some months after my first 8C+ Boulder – Drop a line – at Cousimbert, but when we came back home after five weeks, despite being some kilos lighter, especially my boulder shape was totally destroyed.

This year we played the game again – this time on the Altiplano in between Chile, Argentina, Bolivia and Peru. And everything should turn out to be different. Despite the fact that we played the game even way longer – four months out of five we spent on 4000m. But this time we didn’t get wrecked.

And we did not only survive, neither. No, we took a long and high flight to a bunch of new (personal) limits: The most beautiful landscapes, the vastest boulder fields, the brightest stars (and coldest nights), the most photogenic lines and, well, the hardest ones as well (not only in a personal point of view).

After our journey to Patagonia in 2016 we had left our bus in Uruguay for 10 months to return to Europe to work and send the kids to the kindergarten. In April 2017 we now picked it up again, crossed the endless Pampa and the rocks of Capilla del Monte near Cordoba to enter the beautiful central Andes with the first slight cover of snow north of La Rioja. We passed by the wines of Cafayate, the ruins of Quilmes and visited the endless sandstone boulders of Brealito at the hight of Salta and on 2500m. Our first small step upon the Altiplano.

The next one then lead us directly on 4200m. Tuzgle. The feared eldorado. The first night with minus 20 degrees, the dizzling sun, the puzzling hight. In the end we got chased away by the haunting wind. Not without sending the third hard boulder of the trip and filming it with flying crash pads and crashing camera tripods.

In the same time – without knowing it yet – this was somehow the end of a five years enduring escape to bouldering. Predominantly due to having small kids and few time. As we entered the place of which we hoped the wind would be less aggressive – Socaire in Chile, just on the other side of the border – I directly understood that this was no place to boulder. And that I would again need a driller (after having offered our driller and spits and stuff to the locals of Piedra Parada the year before). Already in Tuzgle there had been some unforgettable lines. In Socaire now there were some more.

And some nice yet equipped projects, too. One of these: Ruta de Cobre, the first 9a of the trip. After 17 tries and a lot of work on finishing the hight adaption, finding out the right breathing techniques, the best regeneration tactics, the ideal nutrition for the almost 4000m of altitude, I could sent it in the first days of June.

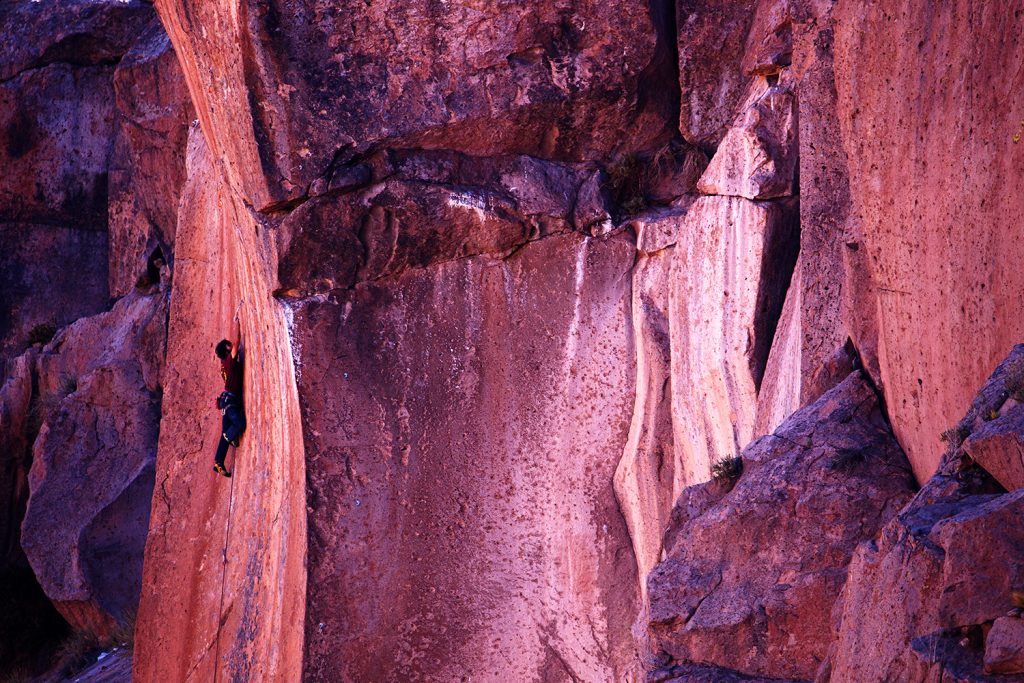

But this was just the warm up on the sunny side of the canyon. During these first four weeks (with a lot of smaller trips to other places in between) I bolted a real highlight on the shady side through a perfect parabolic wall. Shiny colours, a perfect lonesome line, proper volcanic rock seamed with smallest pockets and a real old school challenge with a 7C+ boulder in a slab. And a super precise 8B crux at the very end in an only slightly overhanging wall. Unfortunately by then it was way too hard. I could link the crux only one single time after about ten tries (and the rest point you have before is a hardly worth its name.)

Anyway there was a meter of snow coming (it was an El Nino year) and so we flew to the south. To the cost. To boulder in Punitaqui and Coquimbo and to fill up the reserves.

When we passed by another time two weeks later on our way north to Bolivia, there was still a meter of snow on the shady side of the canyon. And only from a little less acclimatisation (that lasts for more or less six weeks) I did not have any chance at all in the project anymore. Just to feel a little better in front of myself, I said: “With at least one month at 4000m and 3kg less, I will give it another try!”

I did not believe that these requirements would be realistic. Despite the beauty of the line and the chance to open the first more-than-9a of Latin America, I already was pushing away this project from my thoughts. Even in best shape I would need minimum three more weeks (and I knew that there was so much more to see).

At least I thought so.

And so we left to the north, sending Rocoto Love (8c+) in Tajgrapata, getting steamed in the wonderful National Parks of Isluga and Lauca, first ascending the four hardest routes of Bolivia (including In this light you look like Poseidon, 9a, in El Eden) and getting a taste of what could be the best boulder field in the world, Valle de las Rocas, if there was water, a city nearby, less wind, less cold, less hight, etc…

And with less than three weeks to go, we hit another time: Socaire. I don’t know why. I wasn’t hoping to send the project with only that few time, but I wanted to check my shape, as well to grade In this light… revisiting something I already had tried before.

The wind had carried me. Alone, I still did not know it. I expected to have to work myself into the crux again, after six weeks of absence, but I sent it (the crux) right away. I expected to have a lot of problems to link this very limt part to the 50 moves below, but already on the second day I fell on the fore last hard move.

But then the storm stopped me. Fortunately, it was just a feint.

It only forced me to rest enough for the final punch. With not more than one week to go and an again unstable weather despite my great shape it wasn’t sure at all to be able to send it. Just some km/h of wind would turn the conditions into too cold and thus when we walked down into the canyon on August the 14th, I felt a little tensed.

The weather was bright, the wind just an ancient tale of the storm one day before. The temperatures low and the night had been a freezing one. Another freezing one. Minus ten? Minus fifteen? Would the rock be too cold, would it turn my fingertips into numb tools? Too numb to feel the tiny holds in the slab and the upper crux?

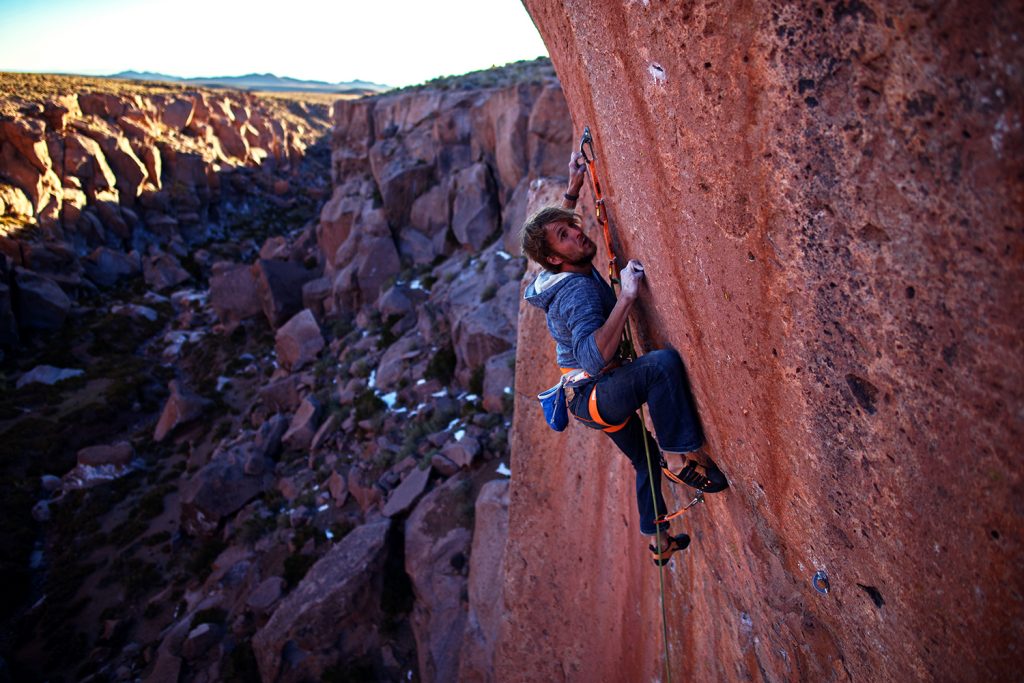

Breathing beneath the route. Something I adapted from yoga techniques. Using the last third of the lungs. 3600m. A microclimate that is supposed to have the same pressure than on 4000m. The first boulder feels well. But it is no reference. Just the 7a+ start. Then another no hand rest on a ledge. Here the route truly begins. The first boulder passes a little belly. Far, technical moves on perfect red rock. Just me and the canyon. A bunch of people below watching the try. Still silently. They know it isn’t serious, yet.

The next five meters are easier, two good rest points. I am still in the slab part of the parabolic shape. I push myself higher, always keeping my breathing in mind. Always checking the feeling in my fingers. The temperature of the rock is hard on the limit, but it is the warmest hours of the day. 2pm.

Comes the hardest slab of my life. 7C+ boulder. High concentration. Non existent food holds. (My climbing partner can’t even charge them at all with his shoes.) Some far, precise moves, followed by a high and very unstable clip. The opening to the hardest moves in the slab. Right hand into the one centimetre deep one finger pocket, the terrible foot hold. I save myself into the following sequence of bad two finger pockets, the wall turns to vertical. Still enough breath, still enough sensation.

I am out of the first crux.

I can’t say if it feels better or worse than five days before. Quite like the same. The rest point still isn’t more than a one and a half digit two finger pocket for one hand and a bad pinch for the other. Almost no feet.

Should I go or should I stay?

Same question three moves further up on an even worse rest point after having clipped the quick draw of the final crux boulder. Slight overhang and the fear of failing. What helps me, is the knowledge that the second go of the day in stamina routes normally is the better one. But less explosive.

I will have to explode in the next three minutes.

Setting the hook on the left, chalking one last time, breathing deeply. “The wind will carry me! I will succeed!” What else can I say with my inner voice if I don’t want to hinder myself? I lock the hook, sled the three middle fingers of my right hand into the pocket-crack. Hard to hit it well. Not that hard today.

The question rather will be: “How long will my reserves carry me higher?” Up to here, everything feels like the last time.

I change the feet from left to right. I assemble my maximum tension for the next double move. The hardest single reach of the route. Three fingers in an again very tight pocket, realigning the body – it is only a 15cm distance to the next hold. But it is the crucial one. I push myself into the next two finger pocket. I hold it. And – what is the most important thing about it – I crimp it. Necessary for the last two hard moves.

It feels like my heart was a machine. My body a metallic device. It feels like I now know that it isn’t impossible any more.

Have I ever missed a chance to fulfil the possible? Only one or two times…

Getting the left foot up, left hand into the crimpy one finger pocket. Right foot a little higher.

Focus!

Then you never have to do it again (in this route).

Then this perfect trip will stay perfect for a the eternal time of episodic memory.

I do. The last move is a jump. Normally. But not today. Very dynamic. But stable. My reserves had been fully loaded by the five days of storm. I am, what I am, somehow again, even at the age of 32, a new climber.

This is a new level. A new sense. This whole thing still is the most thrilling adventure I could have been thrown in.

Does life never get boring?

This is the first time a high end climber has played the Altiplano game over such a long period. The greatest boost in shape and strength since I am fourteen years old.

Six weeks ago this here seemed impossible.

Now I am clipping the anchor. I am crying and shouting. The people 30m lower as well. Later, I’ll be hardly able to speak. The Salar lies silently down in the valley.

Le vent nous portera is fulfilled. The hardest route of South America. But this is just a general consideration.

In the core this is again a purely personal story. The wind has carried us. The four of us. Our family. These pictures, the moving ones, the living ones, are only in our brains. Are ours. Our lives. Our memories.

Our memories of love.